When they stop asking, we're done

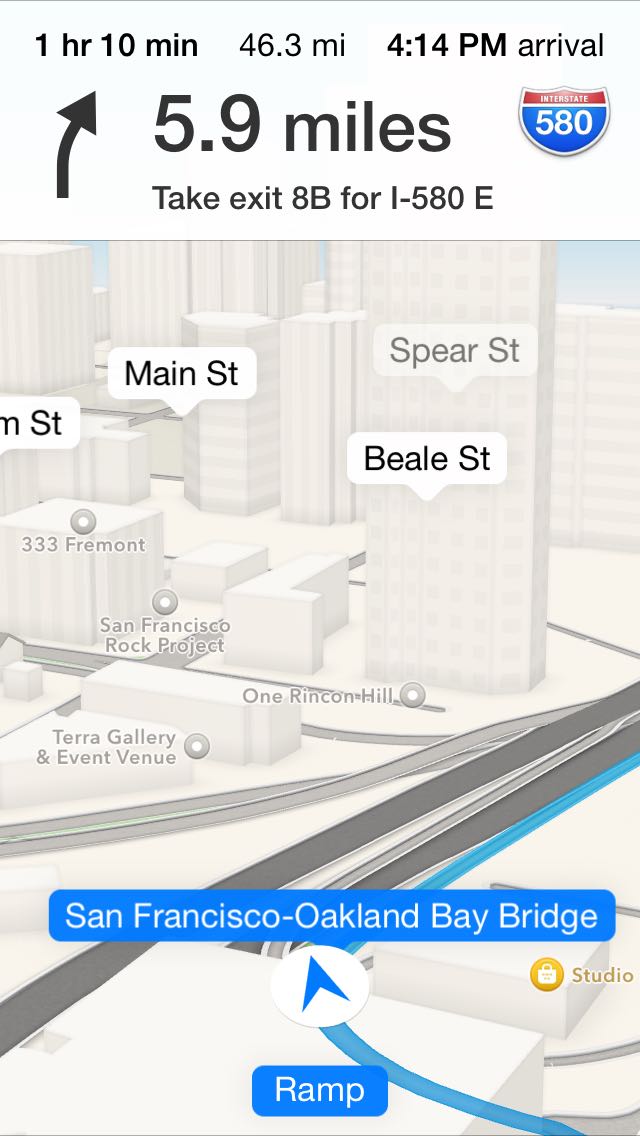

Today's story was about a Norovirus outbreak on a cruise ship that had returned to San Francisco after a 15-day trip to Hawaii. The goals were pretty straightforward: get passengers and video of the ship.

5pm live shot with the cruise ship in the background.

Because the ship's capacity is about 2,500, there were thousands of people getting off the ship, and thousands waiting to get on, so no problem finding people to talk to. But it struck me, every time I spoke to people who were about to get on the ship, they pumped me for information. I identified myself as a local TV news reporter, and instantly, they assumed I knew everything about the virus, how many people got sick, how it was being cleaned up, what precautions the on-board crew was taking. Gratifyingly, I knew a lot of the answers.

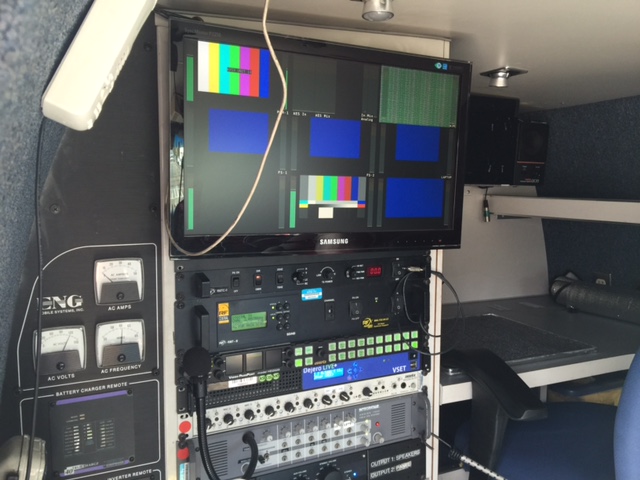

It reminded me how the public assumes journalists are in the know. That's a good thing. The minute people walk past a TV news truck and don't bother asking, "What's going on?" we're done. I always tell young TV reporters and videographers, and even experienced ones, we should welcome inquiries from the public. Engage the public, strike up conversations with passersby, show little kids all the buttons and monitors. We can't survive if people don't care what we know.

One of the passengers I spoke to told me she received an email from the cruise line warning her of a delayed departure, because the ship was being scrubbed to get rid of the virus. Rather than just note that for my story, I asked her if she could forward me the email. She hemmed and hawed a little about using up some of her phone's travel data plan, but finally did it. Beginning reporters sometimes worry they're being too forward or too intrusive by asking for personal things. But it never hurts to ask. The person you're talking to can always say "no." Better to try than to never know if you could have gathered an extra element for your story.

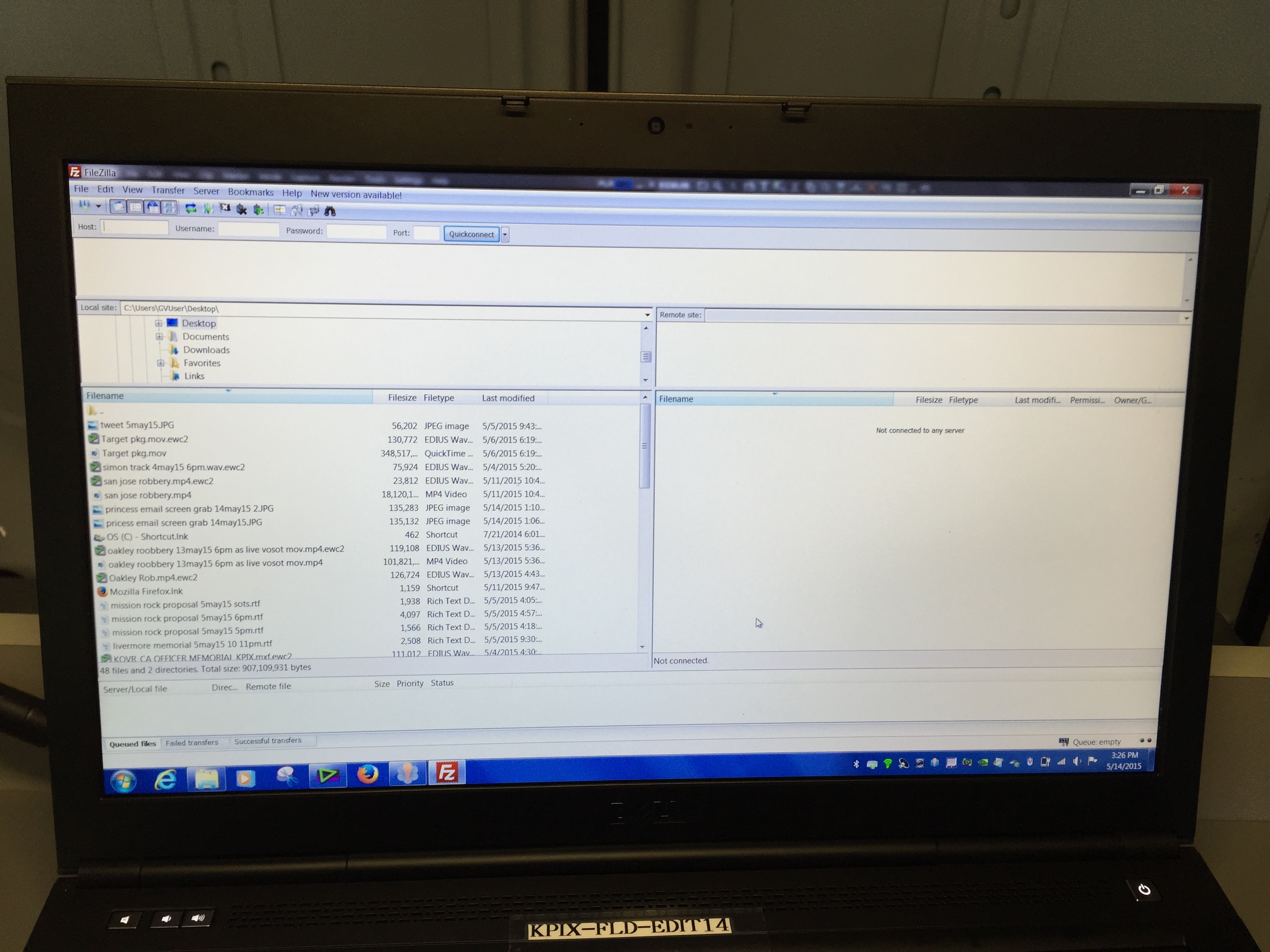

Newhouse students should know they're working with pretty much the same equipment we use in San Francisco. The cameras are a slightly different version of the Sony NX5U, the Adobe Premiere non-linear editing software is comparable to Edius. Even the remote server is recognizable to students: FileZilla. You're getting real-life training at Syracuse.

One of the great things about TV reporting is, no matter how well or how poorly you did that day, once the live shot's over, there's nothing you can do about it. It's OVER. You get a chance to unwind, ponder how you'd do it differently the next time and start thinking about the unpredictable adventure that awaits tomorrow.

Finished!

Takeaways:

- Be nice to the public, AKA our customers. When they don't care what we do, we're toast.

- Ask. The worst that can happen is you get a "no."

- Don't beat yourself up at the end of the day. You can't do anything to change what's happened. Instead, learn from your mistakes and enjoy the fact your TV reporting job allows you to try again tomorrow.