Once is faster than twice

Deadline, deadline, deadline. Absolutely, positively have to make it. Until you've been under that pressure, it's hard to explain the feeling. It can be overwhelming. But, in those situations, when you can almost physically feel every second tick by, it's important to remember to stay calm. The one thing you don't want to do is make a mistake you have to correct. So go slowly, methodically through all your steps in shooting, writing, editing and sending back to the station. Avoid making a mistake and having to repeat a step. Once is always faster than twice.

Today's story was about a new construction project going up in Oakland. It promises to be huge - as in a million and a half square feet of office space. That's more than the SalesForce Tower in San Francisco. The SalesForce Tower is, depending upon whom you ask, the tallest or second-tallest building in the United States west of the Mississippi River. Check out how much taller it is than everything else in the San Francisco skyline in the photo from the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. So when something's bigger than SalesForce, it's news and fits one of the three elements I tell students to look for in a story:

- So what (what difference does it make): just saying the phrase "bigger than the SalesForce Tower" gets the viewers' attention - it's interesting. But there's also the business element of how so much office space might change Oakland.

- Real people (the people living the story): this would be the people occupying the building, but since it's not finished yet, those people would be hard to find. So, instead, I went with an urban planning expert.

- Show me, don't tell me (video): again, difficult because the building hasn't been built yet. But, I could shoot the location and use renderings of what the building is expected to look like.

UC Berkeley City and Regional Planning faculty.

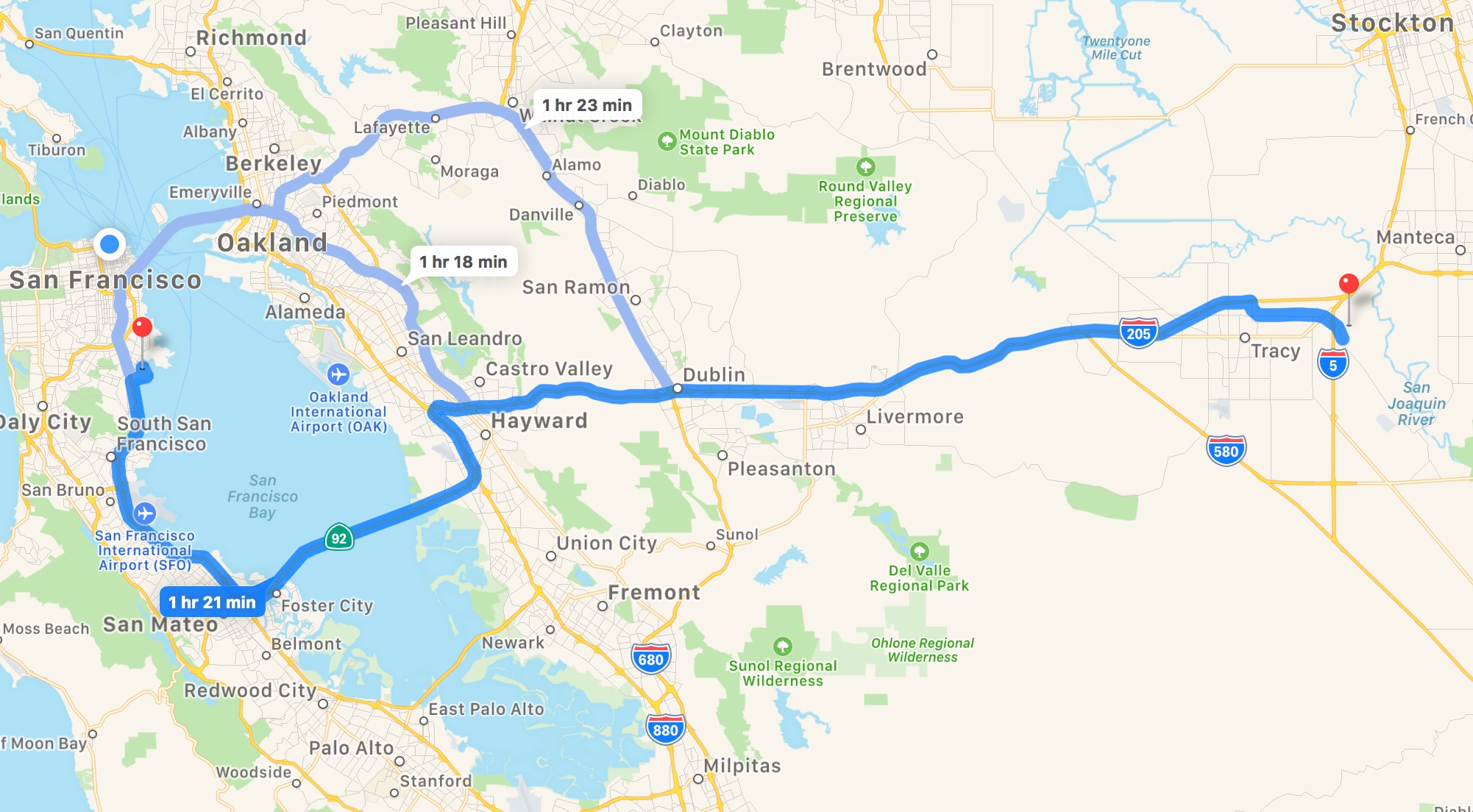

The location where the building was going to go wasn't going anywhere, so I first dedicated my efforts to finding an urban planning expert. The University of California at Berkeley College of Environmental Design has a Department of City and Regional Planning - perfect because Berkeley is right next to Oakland. And with this long list of professors, surely I could find one. So I sent out a blanket email to 15 people I thought might be able to help. I got one immediate out-of-the office reply. One other got back to me and said he'd help. So I was on my way.

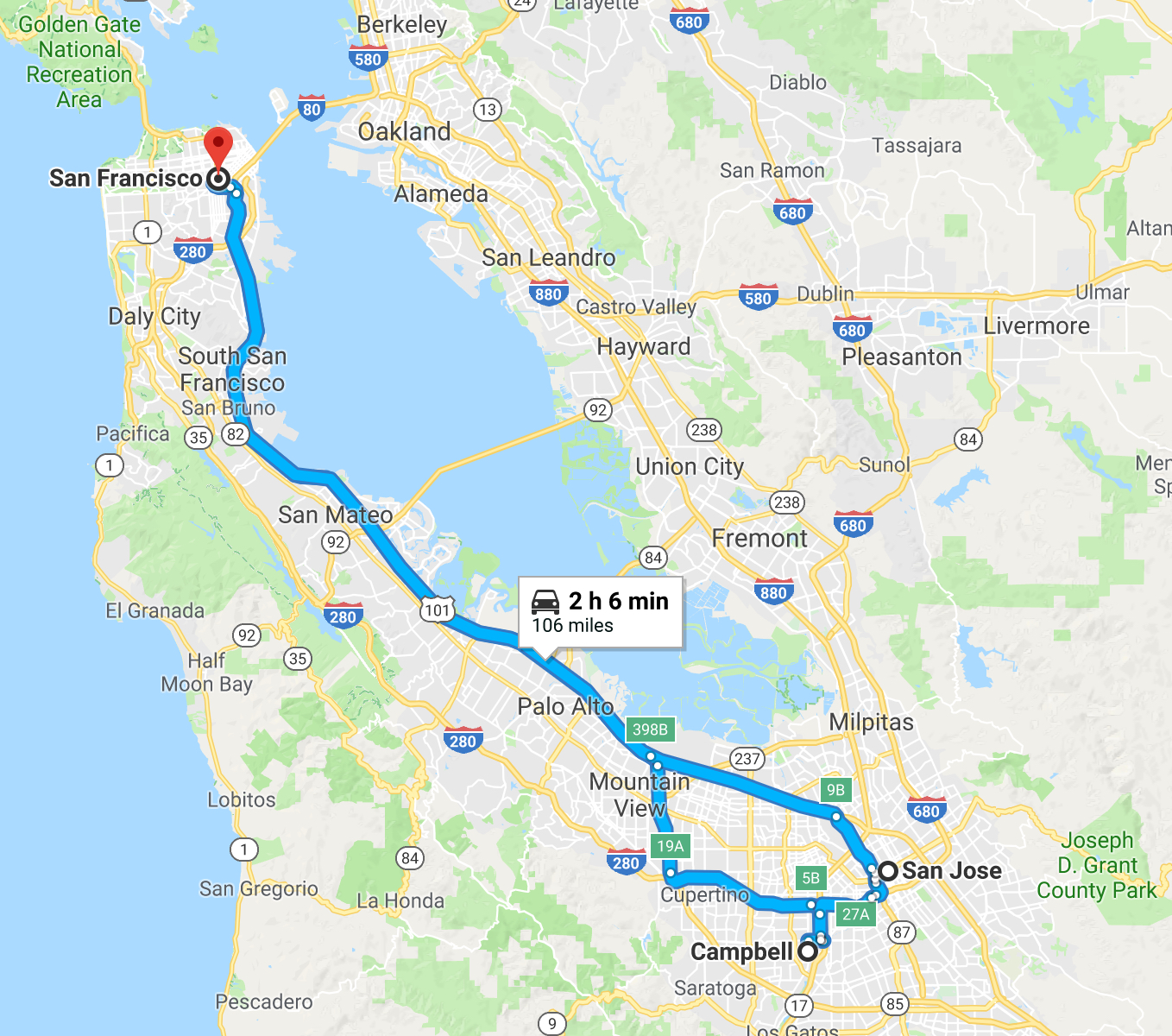

By mid-afternoon, I had video of the location and a standup, but I was still searching for information about the construction project itself. There were lots of groups involved in pulling this project off: real estate developers, investors, designers, public relations firms, the City of Oakland Planning and Zoning Department. I called everyone and was striking out badly. At 4:45 p.m., I was still searching for information. I hadn't reviewed the interview or the video I'd shot. I hadn't begun editing. And my story is in the 6 p.m. show. This is really late. So, I decided to limit the information in my story to what I could confirm from the websites of the people involved in the project: square footage, footprint, goals. So, now it's time to edit, and my heart is racing. I am the lead story in the show.

It's in this moment - where panic is the natural reaction - that TV journalists have to force their minds and bodies to do the opposite. Calm. Control. Focus. Hurrying leads to mistakes and any mistake only means taking time to correct it. Time is the most precious thing you have, the one thing you can't waste on deadline. Beginning reporters must keep in mind, when time matters most, when you're pushing deadline, slowing down and avoiding mistakes is actually faster. As your blood pressure rises, remember once is faster than twice.

Former Oakland Police Officer Andrew Mallory accompanied me as an armed guard for today's story.

Once again I was accompanied by an armed guard to the story location. Oakland was where reporters first started getting harassed and robbed of their equipment. It's now spread to other parts of the Bay Area, but Oakland is usually one of the places that security is always required. A Google search for tv+news+crews+robbed+in+Oakland turns up nearly a million hits.

The hard part about doing a story about something that doesn't exist yet is you can't shoot it. Duh. But if "show me, don't tell me" is one of the essential elements of a TV news story, it's up to the reporter and videographer to figure out some way to do it. In this case, I worked with KPIX videographer Alex Montano, who's also a certified drone operator. (More on his drone work here.) We decided to do a standup that revealed the size of the footprint of the building. This could only be done with a drone. Below is the raw video that shows all three takes. We recorded the audio on the regular video camera via a wireless microphone. And then matched that audio to the video from the drone. The way you do that is with the visual countdown and clap you see at the beginning of the video below. Line up the claps on the audio from the regular camera and the video from the drone and you've got them synchronized. A side note: on the third take, you can see the woman sidles up next to me. I didn't even notice her until after half way through the standup. That's how much a reporter concentrates and can become vulnerable to ne'er-do-wells. She didn't hassle me at all, but it shows why security is a good idea.

Raw drone video of all three takes of the standup showing the footprint of the Eastline project in Oakland.

There's a lot of planning that goes into a newscast. That planning starts in the morning meeting, where managers and reporters discuss ideas. But there's more to it than just the topic. Everyone on the team needs to know the specific focus of the story, who's being interviewed, who's reporting, what the format of the story is, from where the story will be reported, whether the reporter will be live, and who will be operating the equipment to transmit the live shot. That's a lot of stuff. But communication is key to a successful newscast. Everyone needs to know what everyone else doing and where. Here's a list of the stories that KPIX covered on Friday, July 6, 2018.

So that's it for my 2018 KPIX experience. Thanks, once again, to all the managers and teammates who allow me to do this and help me to be successful. The chance to bring up-to-date television newsroom experience back to the classroom really is priceless. And to get to do it in San Francisco is pretty awesome, too.

Some parting shots of the City by the Bay:

Takeaways:

- It's frustrating when people don't call back, but you can't let it get to you. It's your job to find the interviews.

- At crunch time, go slowly and avoid mistakes. Once is faster than twice.

- Drones are cool.

- Putting on a newscast is like directing a symphony. Everyone has to know what everyone else is doing.